In February, the Kingdom of Morocco suspended diplomatic relations with the European Union. This extreme measure was taken in response to a December 2015 ruling by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) to suspend an agricultural trade agreement between the EU and Morocco because it included the Western Sahara (WS) within its territorial scope. While relations appear to be in a dire state, the row is almost certainly temporary – and in fact, it may provide an opportunity to create the collective pressure needed to nudge Morocco towards a more just solution of the WS issue.

The CJEU invalidated the trade agreement on the grounds that the European Commission had not conducted sufficient due diligence to ensure the deal did not violate the rights of Saharawis – the Western Saharan people – over the farming and fishing resources in their territory. The European Council began the process of appealing the CJEU ruling in February. Federica Mogherini, the High Representative of the EU for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, has stated that “the agreements between Morocco and the European Union are not a violation of international law and as such an appeal has been filed, the agricultural agreement otherwise remains in force”.

The EU’s position on the Western Sahara

The EU has not taken a coherent position on the legality of the status of the WS, or on Morocco’s claims to it; instead, it has prevaricated. The EU has not recognised the POLISARIO Front (the Saharawi rebel nationalist movement) or the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), but neither does it explicitly recognise Morocco’s claims to the WS. This ambiguity results from the need to maintain cooperation with Morocco as a stable ally on counter-terror operations and migration flows, while also not appearing to flout issues of human rights, democracy, justice, and African decolonisation.

EU member states have differing stances, coloured by their own interests in bilateral relations with Morocco. France, for example, holds that Morocco’s attempts to devolve some power to the Sahara are credible. It says that bilateral negotiations ought to be continued, and that any divergence from this could negatively affect the relationship between France and Morocco. France is Morocco’s second largest arms supplier after the United States, and it has come to be Morocco’s biggest supporter in the EU. France has also threatened to use its United Nations Security Council (UNSC) veto power if the United Nations should favour a solution that undermines Morocco’s position (which has led observers to conclude that France is partly responsible for the current impasse at the UNSC on the issue).

Spain’s policy is slightly more complex: there is a sense of “collective guilt” for the failure to leave behind infrastructure in the WS and to engage in more decolonisation efforts upon Spain’s withdrawal in 1975, as mandated by the UN at the time. Instead of holding a referendum on self-determination, it signed over the Western Sahara to Morocco and Mauritania in the Madrid Accords of 14 November 1975; Mauritania relinquished its claim in 1979. Spain has also been interested in improving its relations with Algeria (which supports the POLISARIO), and has led it to tacitly encourage the POLISARIO and support the possibility of a referendum. At the same time, however, Spain’s interests in the resources in WS date back to its own occupation of the region, which incentivise preserving good relations with Morocco to ensure access to these resources. Spain’s wish to maintain control over its enclaves, Melilla and Ceuta in northern Morocco, and to cooperate with Moroccan authorities to keep migrants away from these Spanish territories, serve as additional motivation to foster good relations.

Germany, for its part, has also vacillated. However, it has argued recently that the delay on the referendum must end, with some deputies from leftist parties in the German parliament calling for an immediate referendum. The Netherlands and Sweden are among the few EU member states to have recognised Western Sahara as an “occupied territory”. Scandinavian member states have drawn Moroccan ire by tacitly backing the WS’s right to self-determination. Most notably, IKEA’s Casablanca opening was blocked in October 2015, after Morocco alleged Sweden was planning to recognise the independence of the disputed territory – which the Swedish government denied. Meanwhile, Denmark’s parliament voted unanimously in June 2016 to discourage “the engagement of public institutions in, and the purchase of goods from, disputed territories such as Western Sahara, and further urges Danish companies to exercise due vigilance, unless such transactions are known to benefit the local population.”

France is Morocco’s second largest arms supplier after the United States, and it has come to be Morocco’s biggest supporter in the EU.

Opposing interests and positions among EU member states is a major cause of the EU’s legal ambiguity vis-à-vis the WS, and the absurd moniker of the region among EU officialdom: a “non-self-governing territory ‘de facto’ administered by the Kingdom of Morocco”. Whereas the CJEU is taking a decisive stance on the legality of Saharawi claims to the WS, the EU’s ambiguous rhetoric has allowed it to continue pursuing trade in the disputed territory.

A return to conflict?

The situation was exacerbated in March, when Morocco forced the UN mission in the WS (MINURSO, charged with monitoring the ceasefire brokered in 1991 between the Moroccan army and the POLISARIO Front) to close its office in the Saharan city of Dakhla and remove its staff from the territory within 72 hours. The dust-up occurred after UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon visited camps for displaced Saharawis, during which he referred to the WS as “occupied”. The diplomatic spat resulted in a delay in Ban’s annual report on the WS, and caused disagreements among the member states of the UNSC as to how to proceed.

UN spokesperson Stephane Dujarric said that Morocco’s behaviour was “in clear contradiction of its international obligations” and represented an affront to the UNSC. Meanwhile, HR Mogherini stated rather opaquely, and in keeping with EU language, that the EU supports UNSC efforts “to achieve a just, lasting, and mutually acceptable political solution that allows the self-determination of the people of Western Sahara in the framework of the arrangements consistent with the purposes and principles of the UN Charter”. This ongoing deferral to the UN signals the EU’s wish to hand over the messy components of relations with North Africa to the global body, and to maintain the EU’s happily non-committal stance regarding the legality of the WS in the short term.

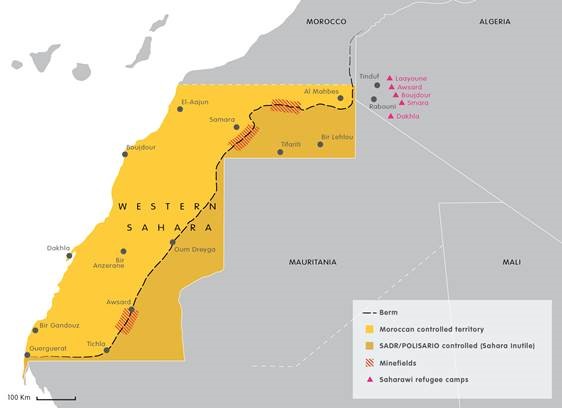

Nevertheless, Morocco’s position has led the POLISARIO to warn of its desire to return to conflict, something that observers of the region have taken with a pinch of salt. The rebel movement has made similar statements more than once in the last several years, using the threat of armed conflict as a little more than a bargaining chip at periods when international attention is heightened. Moreover, their meagre financial backing and military weakness makes them little match for the Moroccan army, which outnumbers POLISARIO forces nearly 25-fold and staunchly defends the berm, the 2,700 kilometre wall that divides POLISARIO-controlled land from the area controlled by Morocco.

Disillusionment among the POLISARIO youth has increased, resulting in higher rates of recruitment into the POLISARIO army and its youth wing, UJSARIO.

However, the UNSC’s inability to fully restore MINURSO’s monitoring capacity after this spat has not sat well with the rebel group. Several observers who have, over the past number of years, accessed the Tindouf camps of southwest Algeria and the POLISARIO-controlled area east of the berm – the largely uninhabited “Sahara inutile” – have recently noticed previously unseen signs that the Saharawi’s may be preparing for conflict. Day-to-day training for POLISARIO troops has become more rigorous, with commanders pushing soldiers to “get ready for battle”. Disillusionment among the POLISARIO youth has increased, resulting in higher rates of recruitment into the POLISARIO army and its youth wing, UJSARIO. And, according to one Dakhla-based Saharawi civil society expert who asked to remain anonymous, “POLISARIO leaders are calling for retired soldiers living in Mauritania and Spain to go back to the camps to fight”. The possibility of renewed conflict would likely have been even greater had MINURSO not been renewed. However, the mission remains challenged and weakened, which likely means that there will be similar flare-ups in the future, especially now that Saharawis’ sensibilities and concerns have been stoked.

Morocco’s plans

Morocco must weigh its interests in extraction in fishing, phosphates, and hydrocarbons with the need to win over the hearts of the Saharawi people, and thereby to minimise resistance. As a result, the Moroccan government has undertaken soft efforts to maintain its hold over the region. These include the recent co-option of formerly pro-POLISARIO and/or Saharawi notables through offering them positions such as wali (governor) of mainland Moroccan provinces as well as ministerial portfolios; a development plan for what Morocco calls its southern provinces; and a proposed autonomy plan for the WS region.

The development plan put forward by Morocco’s Economic, Social, and Environmental Council (CESE) touts billions of dollars’ worth of investments in developing the region, especially in agriculture, tourism, fishing, and phosphates. As part of the effort to develop the WS, Morocco has built airports, paved highways, and improved electricity infrastructure. Simultaneously, however, Morocco has settled thousands of people from Morocco proper to influence the results of a future referendum and to work on farms, which has also stifled opportunities for Saharawi employment and funnelled returns to the Moroccan business elite and the palace. For example, Saharawis once comprised a majority of the workforce in the phosphate industry, but today, they have been replaced by Moroccans. Several companies have halted importation of phosphates from the WS because of the ethical implications of extraction and export, as well as their contravention of international law. These include Norwegian fertiliser company, Yara, which was forced to stop extraction in 2005 due to domestic pressure, as well as US fertiliser company, Mosaic.

The autonomy plan has come to be implemented under the aegis of advanced decentralisation, an ambitious plan to devolve more power to locally elected provincial governments. On its surface, the autonomy plan appears “serious, realistic, and credible”, according to the US government. In fact, these three words have become almost clichéd in the extent to which they have been reprinted and even quoted out of context by Morocco and its interests when referring to its vision for the WS. But the autonomy plan, which is more or less under way under decentralisation, allows Morocco to avoid the self-determination referendum mandated in the original ceasefire agreement of 1991, and the EU has failed to hold Morocco accountable for this evasion.

Even if local elections are free and fair, Saharawis both inside and outside POLISARIO-controlled territory, as well as within Morocco itself, remain sceptical at best about the corruption and nepotism surrounding elected local presidents (who have absorbed some of the prerogatives of the palace-appointed walis), and about the extent to which local presidents’ hands will be tied, with their interests linked to and checked by the palace – precluding a genuine chance for real change. Moreover, the decentralisation would split up the WS into three regions, one of which will include land that is part of undisputed Moroccan territory.

These reservations have led the SADR to reject autonomy as cosmetic and nominal. It is weary of accepting concessions that lead to placation in the short term, and perhaps co-option in the longer term, while deeper concerns such as greater control over the lucrative oil, phosphates, fishing, and agriculture resources remain unresolved. These concerns are compounded by Morocco’s decades-long unmet promise to hold a referendum on self-determination.

The EU’s future course

How sustainable, then, is the EU’s ambiguity? How long can it juggle its desire to pursue easy relations with Morocco, privileging cooperation on various fronts, with the WS issue? It will take time and finesse, but the EU could take gradual steps to clarify its legal stance on the WS, a position that ought to guide its bilateral relations with Morocco under international law. This position should make clear, firstly, that the delayed referendum is itself a challenge to the region’s stability and, secondly, that trade agreements should exclude products from the WS (which need not preclude trade with Morocco, especially as the Kingdom stands to gain much more than the EU, and since the US-Morocco FTA does not include products originating from the WS). The EU should also reiterate to Morocco that it is in everyone’s interests to uphold international law, while also maintaining the alliance, and to exchange intelligence on domestic terrorists, migrants to Europe, and the large volume of Moroccans migrating to join the Islamic State group.

Morocco knows that it is in a relatively strong bargaining position vis-à-vis the EU. It is a stable ally, a key trading partner, a safe and cooperative North African country committed to countering terror.

Given events in the region, cooperation is no doubt a key consideration in EU policy-making. However, those interested in the region’s stability should not be beguiled by misleading rhetoric that (a) inflates the security threat facing Morocco (because it does not threaten Morocco alone) and its ability to confront it, (b) conflates Saharawi resistance and Islamist terror groups in the region, (c) plays down the safety and (human) security of the WS itself in the interests of that of Morocco, and (d) argues unquestioningly and without empirical evidence that a free WS would be a “failed” or “weak” state.

Indeed, Morocco’s aggressive and costly lobbying efforts in the European capitals have sought (with a good deal of success) to discourage the inclusion of greater territorial conditionality in agreements that cover the WS. Such efforts have also promoted perceptions that al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) actively recruits in the POLISARIO-run, UN-administered Tindouf camps. While there is a real possibility that disenfranchised persons might be drawn to smuggling activities and perhaps extremism, this does not translate into collusion between the POLISARIO and AQIM. This claim, often levelled by Morocco and its lobby, has not been substantiated through any primary source material; instead, analytical “cliques” and self-referencing abounds in the peddling of these narratives.

There is moreover an important contradiction in this argument, one that is key for the EU to note, and that has been long overlooked by those who subscribe to the above logic. If Morocco truly believed or was truly anxious about the (specifically Saharawi) vulnerability to radicalisation and recruitment, it would seem prudent for it to prioritise a sustainable solution. Such a solution should empower the disaffected people in the region, end the standstill by holding a referendum that would appease the supposedly at-risk population, end the destitution of Saharawis in the camps, and yield returns on the resources of Saharawis living west of the berm.

Morocco knows that it is in a relatively strong bargaining position vis-à-vis the EU. It is a stable ally, a key trading partner, a safe and cooperative North African country committed to countering terror, and the EU’s gatekeeper against undocumented sub-Saharan African (and now Syrian/Iraqi) migrants – especially as Morocco is willing to play “bad cop” and enact the sort of heavy-handed migrant policies from which the EU benefits.

Morocco’s suspension of diplomatic relations with the EU appears to be little more than a temporary flexing of this muscle – to remind the EU of its “red lines” and discourage the logic behind the CJEU position. It is primarily symbolic, as the Moroccan leadership continues to meet with EU delegates and with Mogherini, and as bilateral relations with individual member states remain intact.

However, Morocco also correctly perceives that it has more to lose in this standoff. To be sure, there will be some damage and hard feelings in the shorter term. But in the medium to long term, Morocco is fully aware of all that its stands to gain from maintaining positive relations with the EU. Morocco worked hard to achieve “advanced status” with the EU in 2008 (and at one time, it hoped for full membership); there is strong evidence that Morocco’s economy stands to benefit more from deeper FTAs than does the EU’s; and the country remains eager to prove its mettle as a counter-terror/migration partner as well as to take credible steps toward becoming a freer country domestically, in order to retain its standing with the EU. It is thus likely to concede, if the EU calls Morocco’s bluff by allowing the suspension to proceed, and is firmer about negating Morocco’s attempts to veto EU measures – particularly when these measures are taken to ensure compliance with international law.

The EU’s trade, security, and migration interests in Morocco challenge its willingness to apply too great a pressure, especially because Morocco has ramped up cooperation and intelligence sharing with French and Belgian authorities after the recent terror attacks in Paris and Brussels – and EU opposition to the CJEU ruling is a product of this hesitance. However, its intentionally vague and fractured policy toward the WS is unsustainable. It should take comfort that the above pillars of Morocco’s carefully curated international image are not ones that the Kingdom will quickly relinquish in the interests of making a statement against the EU or against Ban Ki-moon’s choice of words.

Morocco has to balance its desire to remain in the EU’s good graces and appear credible in its steps to improve its human rights record with its desire to maintain its grip on a region that is lucrative to Moroccan business interests and central to Morocco’s statecraft and to the monarchy’s legitimacy. The Kingdom’s political signals need not alarm the EU. In fact, the CJEU rulings and the likely period of “mending fences” may provide just the opportunity needed to clarify the EU’s position on the WS and to take a more decisive, coherent and less passive stance on the issue. Each time the EU backs down in the face of Morocco’s conniptions, it loses the chance – and the momentum – to gradually and peacefully break the impasse.